When studying the effect of treatments in real-world data, one of the biggest challenges is bias from confounding variables. Unlike randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies do not assign treatments randomly. Certain patients might have characteristics that make them more likely to receive a particular treatment, such as age, disease severity, or lifestyle factors. To reduce this bias, researchers often use a powerful statistical tool called the propensity score (PS).

What Is a Propensity Score

The propensity score is the probability that an individual will receive a particular treatment, given their characteristics (covariates). It was first introduced by Rosenbaum and Rubin in 1983 to create a quasi-randomized setting in observational studies. If two individuals have the same PS, their background characteristics are assumed to be similar, which makes comparing outcomes between them more reliable.

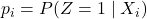

Formally, for an individual ![]() with covariates

with covariates ![]() , the propensity score is defined as:

, the propensity score is defined as:

![]()

Here:

indicates that the individual received the treatment,

indicates that the individual received the treatment, means the individual did not receive the treatment.

means the individual did not receive the treatment.

Why Propensity Scores Are Useful

In randomized trials, random assignment balances both observed and unobserved variables between groups. But in observational studies, this balance does not naturally occur. Propensity scores aim to mimic randomization by ensuring that individuals with similar scores are compared, reducing the impact of confounding variables.

For example, consider a study comparing two drugs for managing diabetes. Younger patients may be more likely to receive the new drug because doctors prefer it for those with fewer complications. If we directly compare outcomes without adjusting for age, the results may be biased. By calculating PS and matching patients with similar scores across the two treatment groups, we can create comparable cohorts.

How to Calculate a Propensity Score

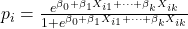

The most common way to calculate PS is using logistic regression, where the treatment variable ![]() is the dependent variable and the covariates

is the dependent variable and the covariates ![]() are predictors. For an individual

are predictors. For an individual ![]() , the PS is:

, the PS is:

![]()

Here:

are the regression coefficients,

are the regression coefficients, are the covariates for the individual.

are the covariates for the individual.

Matching Using Propensity Scores

Once propensity scores are calculated, they can be used to create comparable groups through matching. Matching ensures that for each treated individual, there is one or more untreated individuals with a similar PS.

1:1 Matching

In 1:1 matching, each treated individual (with ![]() ) is paired with one untreated individual (with

) is paired with one untreated individual (with ![]() ) who has the closest PS. A simple example is greedy matching, where a treated subject is matched with the nearest control subject. This process is repeated until all treated subjects are matched.

) who has the closest PS. A simple example is greedy matching, where a treated subject is matched with the nearest control subject. This process is repeated until all treated subjects are matched.

M:1 Matching

In some studies, you may want to match multiple untreated individuals to a single treated individual. For instance, a 1:2 matching pairs each treated subject with the two untreated individuals who have the closest PS.

Optimal Matching

Optimal matching aims to minimize the total difference between PS values of matched pairs. While it is computationally more intensive, it often achieves better covariate balance compared to greedy matching.

Caliper Matching

To ensure good quality matches, calipers (thresholds) are applied. A caliper sets the maximum allowed difference in PS between a treated and untreated individual. If no suitable match is found within this threshold, the treated subject is excluded from the analysis. A commonly recommended caliper width is:

![]()

This means 20% of the standard deviation of the logit-transformed PS.

Example of Matching in Practice

Imagine a hospital study comparing patients treated with Drug A and Drug B. Suppose we have 500 patients on Drug A and 1,000 on Drug B. After calculating PS, each patient on Drug A is matched with a patient on Drug B who has the closest PS within a caliper distance of 0.01. The final matched sample might include 480 pairs where covariates like age, weight, and comorbidities are well balanced between the groups.

Alternative Uses of Propensity Scores

- Stratification: Subjects can be divided into groups (strata) based on PS values. For example, you can divide subjects into five quintiles of PS. Within each stratum, treated and untreated individuals are compared, and the results are combined across strata.

- Covariate Adjustment: The PS can be included as a covariate in a regression model to adjust for confounding. However, studies have shown that this can sometimes produce biased estimates, especially if PS distributions do not overlap well.

Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (IPTW)

In IPTW, each individual is assigned a weight that is the inverse of the probability of receiving the treatment they actually received. For an individual ![]() , the weight

, the weight ![]() is:

is:

![]()

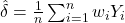

The average treatment effect (ATE) can then be estimated as:

![]()

Here, ![]() is the outcome for individual

is the outcome for individual ![]() .

.

Example of IPTW

Consider a study on the effect of a blood pressure drug. If a patient has ![]() (80% chance of receiving the drug) and actually receives it (

(80% chance of receiving the drug) and actually receives it (![]() ), the weight is

), the weight is ![]() . For a control patient with

. For a control patient with ![]() , the weight is

, the weight is ![]() . These weights are used to create a pseudo-population where treated and untreated groups have balanced characteristics.

. These weights are used to create a pseudo-population where treated and untreated groups have balanced characteristics.

Limitations of Propensity Score Methods

While PS methods are powerful, they have limitations:

- Dependence on Covariates: PS can only adjust for observed variables. Unmeasured confounders still create bias.

- Overlap Requirement: There must be sufficient overlap in PS values between treatment groups.

- Large Sample Needs: PS matching or stratification can fail in small datasets, where achieving covariate balance is difficult.

- Extreme Weights: In IPTW, very small or large PS values lead to extreme weights, which can destabilize the estimates.

High-Dimensional Propensity Scores (hd-PS)

Traditional PS models may struggle with high-dimensional data (many variables). The hd-PS method includes a large number of variables, such as diagnosis codes, medications, and procedures, ranking them by their potential to confound the relationship between treatment and outcome. However, hd-PS requires careful selection of variables and can be computationally heavy.

Modern Machine Learning Approaches

Machine learning algorithms have been applied to estimate PS more effectively, especially when data has many variables or non-linear relationships. Examples include:

- Neural networks, which can model complex patterns in data.

- Random forests and gradient boosting, which are ensemble methods that perform well with large and noisy datasets.

These methods reduce reliance on logistic regression and can improve matching quality, but they require careful tuning and validation.

Sensitivity Analysis and Balance Checking

After applying PS methods, it is important to check that the treatment and control groups are well balanced. A common measure is the standardized mean difference (SMD) for each covariate. A rule of thumb is that the absolute SMD should be less than 10% for all variables:

![]()

Where:

and

and  are the means of the covariate in treated and control groups,

are the means of the covariate in treated and control groups, and

and  are the standard deviations.

are the standard deviations.

When There Are More Than Two Groups

Propensity score methods are more complicated when there are multiple treatments. One approach is to perform pairwise PS matching for each treatment versus a common control group. For example, if you are comparing three cancer drugs and a placebo, you can build three separate matched datasets: Drug A vs placebo, Drug B vs placebo, and Drug C vs placebo.

Key Formulas Recap

-

Propensity Score:

-

Logistic Regression for PS:

-

Inverse Probability Weight:

-

Average Treatment Effect:

-

Standardized Mean Difference: